The Indian National Congress (Congress) under the direction of Gandhi led the struggle for India’s independence from Britain, appealing for patriotism across religious divisions. While these divisions had long existed, they were made significantly and deliberately worse by the British administration since India’s First War of Independence in 1857. Started as a mutiny by the Indian soldiers of the British army in India, the conflict grew into a powerful struggle, uniting rulers of various princely states (most of them non-Muslims) behind the last Moghul king Bahadurshah Zafar (a Muslim). As a result, the time-tested policy of Divide and Rule was launched. It manifested itself in state decisions, such as the Partition of the state of Bengal into Muslim and Hindu dominated territories, and also in covert operations, such as promoting right-wing elements.

It is no coincidence therefore that both Hindu and Muslim separatist organizations were founded within a few years of each other by individuals who opposed the joint struggle against British imperialism. The All-India Muslim League (IML) was founded in 1906 by the Muslim elite mainly to promote western education in Muslims and for protection of the rights of upper class Muslims. In 1910, the All India Hindu Conference was held by some upper caste Hindus to encourage Hindu political unity and reconversion of Muslims to Hinduism. This led to the formation of The Hindu Mahasabha (HM) in 1914.

Although seemingly opposed to each other, both these organizations cooperated with the British and subverted the independence movement. They even formed coalition governments in three states in 1942 under the auspices of the British administration. This was during the Quit India Movement with nearly 60,000 in jails including the entire leadership of the Congress. The two religion-based organizations were meanwhile appealing to support the British in the Second World War. Savarkar, the leader of HM, called to every “Hindu who is capable to put in military service”[2].

The partition of India along religious lines by the British in 1947 was in every aspect a negation of the inclusive spirit of the freedom struggle. IML succeeded in its demand for an “Islamic” state in the form of Pakistan despite the majority of Indians and majority of Indian Muslims opposing it. Over 12 million people were displaced and nearly a million killed. While few Hindus remained in Pakistan, a large number of Muslims stayed back in India and some even left their homes in Pakistan to join India. This became possible because India chose to be a non-theocratic state under a secular.

In opposition to the secularism of the Congress, the MS wanted to mirror Pakistan in forming a theocratic state in India. Savarkar went so far as to declare that the king of Nepal, a Hindu kingdom at the time, had the “best chance of winning the Imperial crown of India”.[3] However, such sentiments had virtually no popular support. In1948, Gandhi was killed by a member of HM, Nathuram Godse. To him, Gandhi betrayed India by appeasing Muslims. That Muslims or any non-Hindus were allowed to live in India as equal citizens was unacceptable. Godse’s "first duty", in his own words, was "to serve Hindudom and Hindus both as a patriot and as a world citizen".

It is almost as if these words have found a new speaker in the form of Modi more than six decades after Gandhi’s murder. But the doctrine of equating Indian nationalism with Hindu nationalism or Hindutva has had its champions throughout these years in the form of right-wing fringe organizations such as RSS[4] and BJP.

According to Savarkar, Hindutva is a racial concept. According to him, all Hindus form a single jati (race) bound by blood and the commonality of faith, tradition and heritage. This makes them a nation and as the origin of their faith is in India, they are pure Indians. Christians and Muslims are not pure Indians as their faiths originated outside of India. By this logic, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists are also Hindus and therefore Indian.

There are many problems with this philosophy. To name just one, the religion and culture of Hindus is not homogenous as there are many castes, sub-castes, regional differences and no single deity that is the most revered by all. In fact, the word “Hindu” does not appear in any ancient texts of what is now known as Hinduism (for instance, the Vedas). It was not until the British conducted the census, that part of the population which did not identify as Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, etc., was collectively referred to as Hindu. In the past, they were identified by castes (Brahmin, Kshatriya, etc.) or by the deity that worshipped (followers of Shiva, Vishnu, etc.). The word Hindu is derived from Sindhu or the Indus river beyond which the present day Pakistan and India are situated.

In addition, any practicing Sikh, Jain or Buddhist would not identify as a Hindu. Apart from the fact that their religions are distinctly different, their heritage can even be called conflicting to that of Hinduism. For instance, a basic originating point of Buddhism is the Buddha’s rejection of the authority of the Vedas and the Brahmins.

Another example is pertaining to diet. Hindutva supporters often cite vegetarianism as a distinct trait of Hindus. Millions of practicing Hindus are traditionally non-vegetarian. For instance, the staple of Bengali Hindus (and Muslims) is fish while Kashmiri Hindus are famous for their traditional meat dishes.

The purity of race is an absurd and dangerous basis for any collective claim such as nationhood but it is next to impossible a foundation for a country like India which is perhaps the most racially diverse in the world. If someone like Godse were to be given the charge of running an Indian state, say Nagaland, he would find that the well being of 90 percent of the population would not be his first duty as they are not Hindus.

The champions of Hindutva are very much a part of India’s political system. But can their brand of nationalism gain enough popularity to become national policy? The far-right has never been able to achieve absolute majority at the national level. The main factor behind it is perhaps the fact that for most Indians, their religious identity is not their sole concern or even the sole characteristic that defines them. The struggle for bread and butter is more important. In addition, Indian heritage is essentially that of racial and religious diversity and cohabitation.

Having said this, independent India’s history is dotted with sectarian violence. Most recently, during Modi’s Chief Ministership of Gujarat in 2002, close to 2000 people, mostly Muslims were killed by armed mobs. The courts found no personal evidence against Modi. However, national and international civil rights organization documented numerous examples of state complacency. According to a report of Human Rights Watch, entitled, "We Have No Orders to Save You", the police had been "passive observers, and at worst they acted in concert with murderous mobs." In the aftermath of the violence, thousands of Muslims left the state and according to Amnesty International, even after a decade, "at least 21,000 persons are still in 19 transit relief camps awaiting relocation". There is a systematic social and economic boycott of Muslims and Christians in the state and the term “ethnic cleansing” has become associated with Gujarat in no uncertain terms.

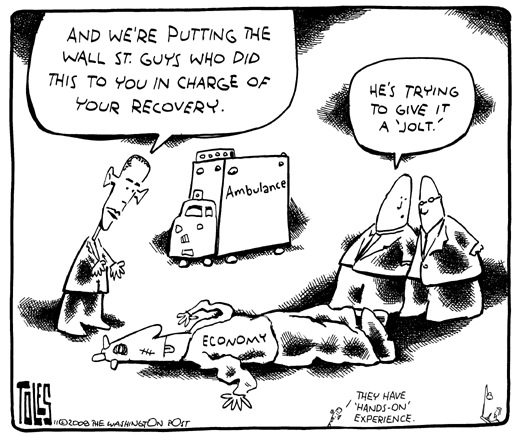

The Congress, which heads the national coalition government, defines itself as secular and opposed to religious sectarianism. This is how it differentiates itself from the BJP. In other respects, however, both parties have failed to fulfill the aspirations of the majority. Basic nutrition, clean water, primary education, safety and housing still remain the unfulfilled promises of yesteryears. Similarly, both parties fully endorse open markets, privatization, deregulation, and decreasing the size of the public sector.

India’s official poverty rate is decreasing, but in many ways this is a trick of the numbers. The official poverty line is so low (27 rupees or $0.45 a day in rural areas) that the official statistics only capture a small picture. But even according to these figures, 1 out of every 5 Indians lives in poverty. Estimates show that there are as many Indians living at risk of hunger and malnutrition as there are throughout the entire African continent.

Neither mainstream party in India offers meaningful policy changes for the poorest. In such desperate times, scapegoating the other community can be a powerful weapon to turn public opinion away from economic hardship and towards the (exceedingly limited) privilege given to the other community either by virtue of their caste, creed or through access to affirmative action-type programs.

This reality, along with anti-incumbency sentiment against the Congress which has been in power for a decade mean that what was once unthinkable is now a distinct reality: Narendra Modi may just become the next Prime Minister of India.

Shirin Shirin is a freelance journalist, activist, and analyst for Foreign Policy In Focus. Her work includes using popular education to campaign against religious violence and promote the rights of women, workers, minorities, and dalits throughout South Asia.

- Shirin - September, 2013

[1] Bhartiya Janata Party is a Hindu nationalist party founded in 1980. Its predecessor was Bhartiya Jana Sangh (founded in 1951), widely regarded as an arm of RSS (see footnote 3).

[2] A.S. Bhide (ed.), Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s Whirlwind Propaganda: Extracts from the President’s Diary of his Propagandist Tours; Interviews from December 1937 to October 1941, Bombay, 1940, p.414.

[3] Ibid., p.256.

[4] Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, an ultra-right Hindu separatist organization was founded in 1925. It is volunteer based and has often been accused of violent actions against people it finds are insulting to its definition of Hinduism. Godse was a former member of the RSS. Narendra Modi was also a member and a pracharak, literally a promoter.